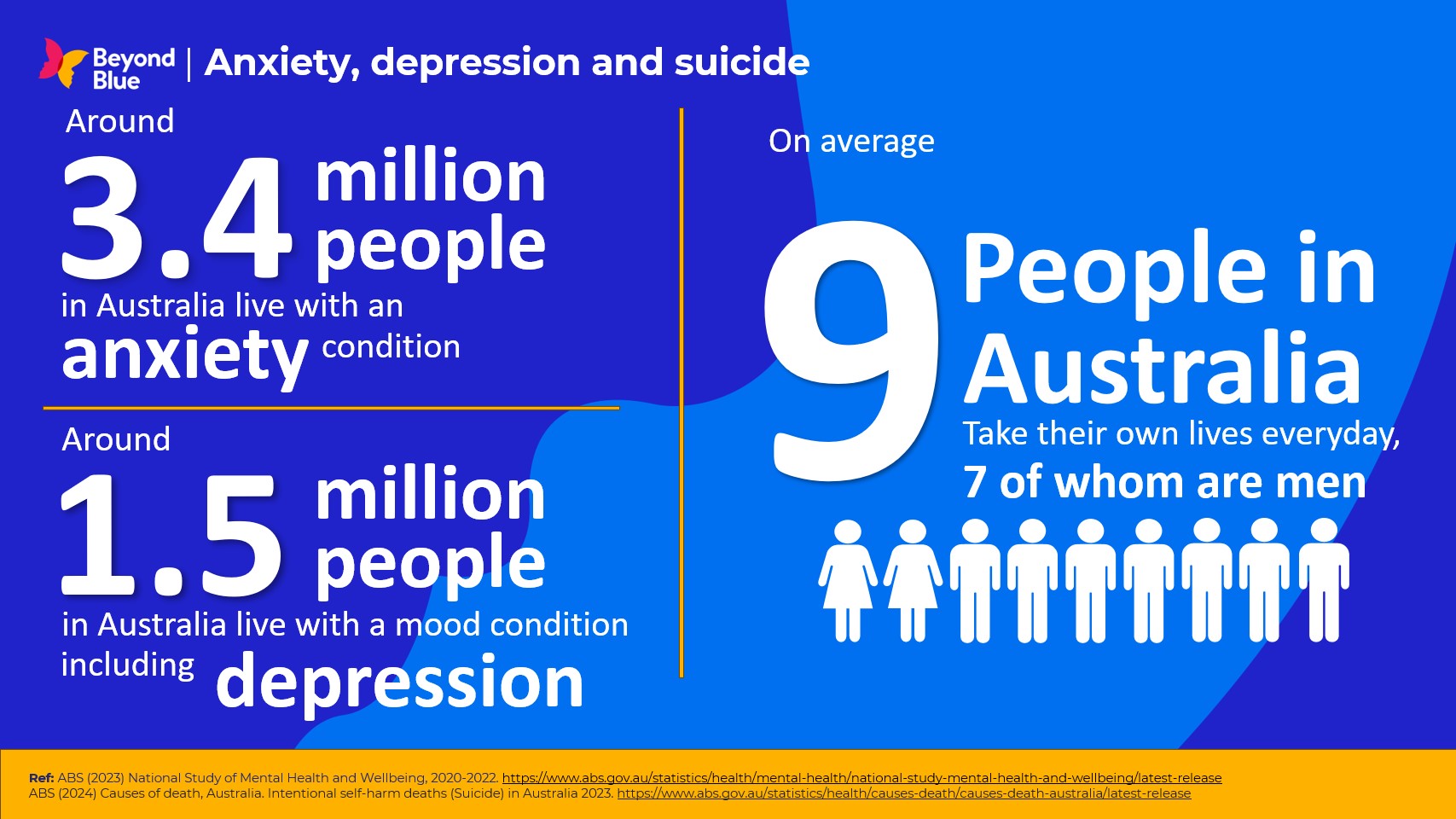

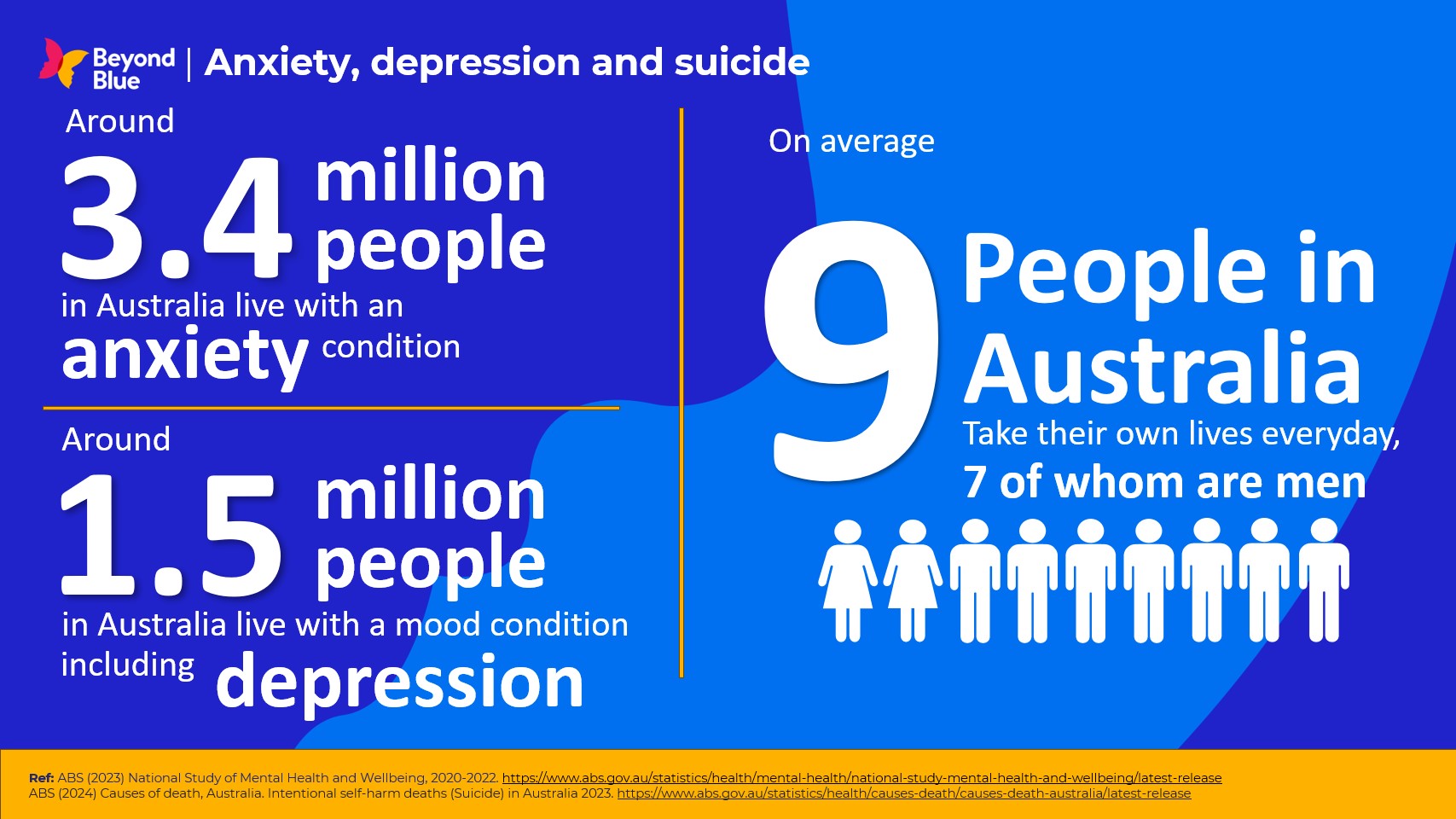

Statistics

Beyond Blue uses statistics from trusted references and research.

View some of our most commonly used stats, or find the relevant category from the list below to find the specific information you're looking for.

Beyond Blue uses statistics from trusted references and research.

View some of our most commonly used stats, or find the relevant category from the list below to find the specific information you're looking for.