Our work with First Nations Peoples

Acknowledgement

Beyond Blue acknowledges the Land on which our head office is based has deep connections to peoples and cultures across the Eastern Kulin Nation. As such we acknowledge the Traditional Owners of this area, the Wurundjeri Peoples, and pay our respects to their Elders past and present. As an organisation with national reach, we extend our respect to all Elders and First Nations Peoples across Australia.

Beyond Blue acknowledges the Land on which our head office is based has deep connections to peoples and cultures across the Eastern Kulin Nation. As such we acknowledge the Traditional Owners of this area, the Wurundjeri Peoples, and pay our respects to their Elders past and present. As an organisation with national reach, we extend our respect to all Elders and First Nations Peoples across Australia.

Beyond Blue recognises that much needs to be done to address depression, anxiety, suicide and related drug and alcohol issues in First Nations Peoples communities.

Over time and across Australia, generations of First Nations Peoples have experienced trauma, grief and loss. Psychological distress is high among First Nations Peoples and this is worsened by ongoing social and health factors.

Beyond Blue works to address discriminatory behaviour and equip First Nations Peoples with the knowledge and skills to maintain their own social emotional wellbeing. This includes recognising signs in people close to them, in order to prevent the development of a mental health condition.

In consultation with First Nations Peoples communities, Beyond Blue has developed a range of research, information, education and support strategies to support the social and emotional wellbeing of First Nations Peoples.

Read Beyond Blue's position on social and emotional wellbeing for First Nations Peoples.

Over time and across Australia, generations of First Nations Peoples have experienced trauma, grief and loss. Psychological distress is high among First Nations Peoples and this is worsened by ongoing social and health factors.

Beyond Blue works to address discriminatory behaviour and equip First Nations Peoples with the knowledge and skills to maintain their own social emotional wellbeing. This includes recognising signs in people close to them, in order to prevent the development of a mental health condition.

In consultation with First Nations Peoples communities, Beyond Blue has developed a range of research, information, education and support strategies to support the social and emotional wellbeing of First Nations Peoples.

Read Beyond Blue's position on social and emotional wellbeing for First Nations Peoples.

Our Reconciliation Action Plan

Our Innovate Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP) supports our journey to learn more about the world's oldest continuing culture and assist us in creating a culturally safe organisation.

"Strength through Connection" by Kalara Gilbert.

Kalara Gilbert is a Wiradjuri artist based in Canberra. Her colourful paintings pay homage to Country. Kalara is passionate about telling stories through painting and bringing awareness and understanding of First Nations Culture.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community controlled health services by state

NPY Women's Council and Ngangkari program

"It’s really important to hold onto that language around how people feel and how they make sense of what they feel, and what they think."

Iframe content loading...

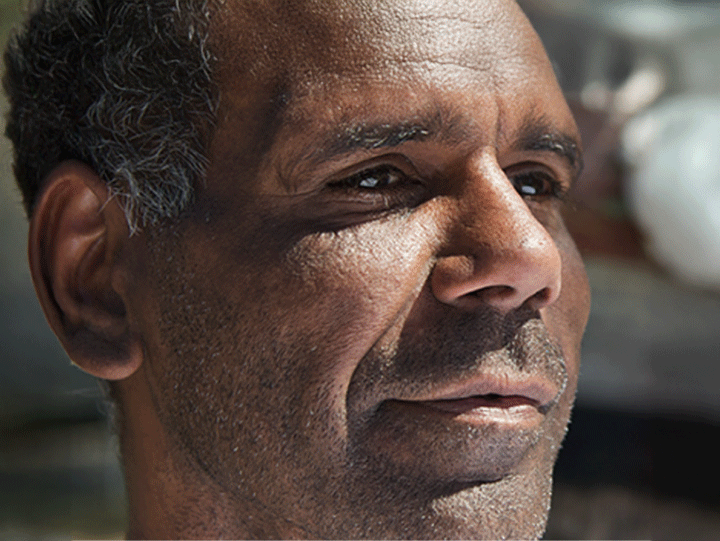

Kyle Vander Kuyp

"However you're feeling, don’t be afraid to reach out, ask for help and share what you're feeling."

Iframe content loading...