Stories to inspire you

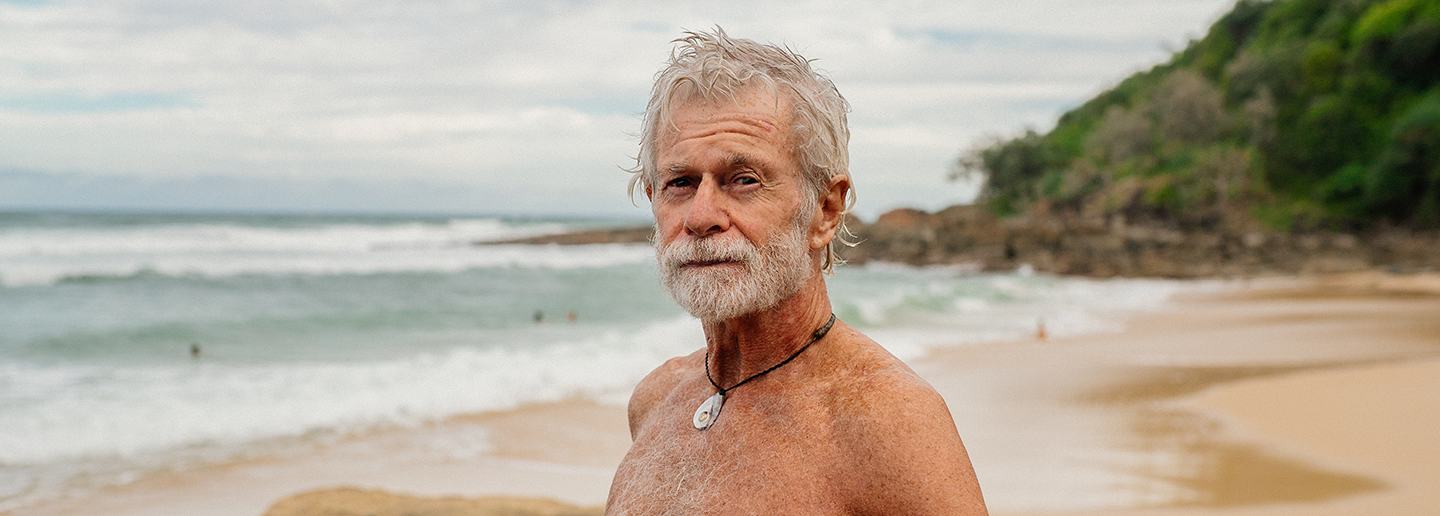

Read, watch and listen to stories from everyday Australians about the signs and symptoms they experienced, how they got support, and what they do to stay well now.

Hearing their stories of recovery can help you imagine your own journey.

What a panic attack feels like - Milli's story

Loading component...

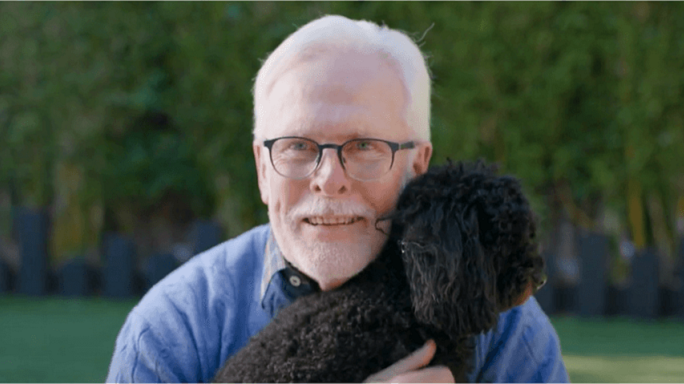

Stories from the LGBTIQ+ community

Sharing personal stories fosters connection, support, and understanding within the LGBTIQ+ community.

Here, individuals share their journeys, highlighting both the challenges and triumphs they have faced.