Stories to inspire you

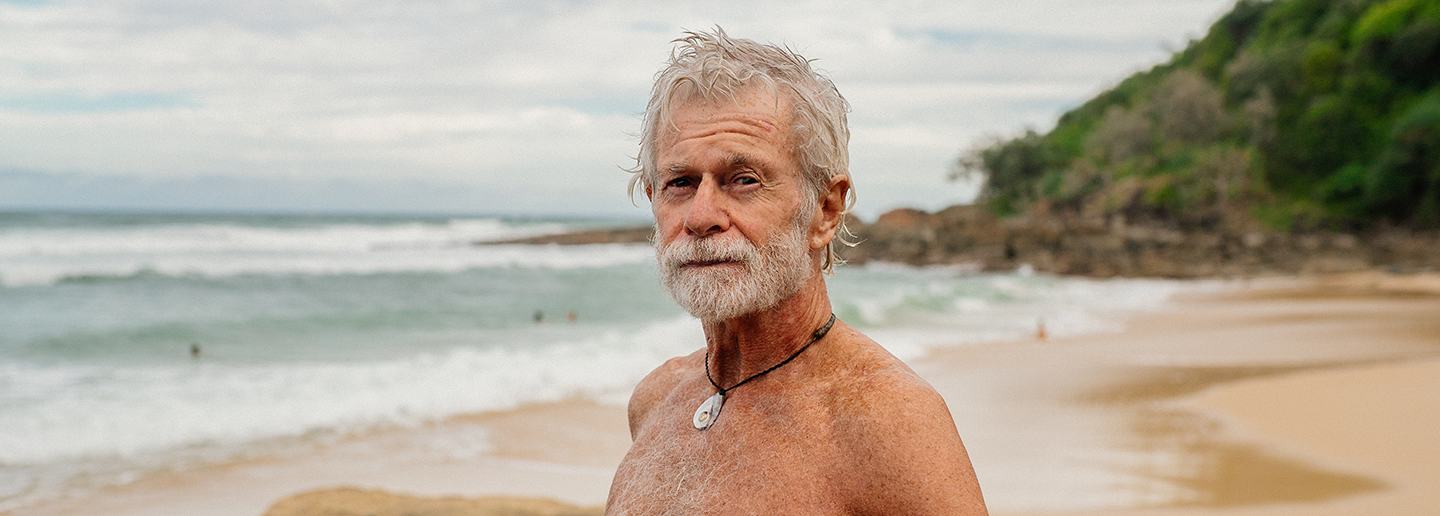

When it comes to mental health, we all have our own unique stories to tell. But no matter what we are going through, there are other people experiencing it too.

Read, watch and listen to stories from everyday Australians about the signs and symptoms they experienced, how they got support, and what they do to stay well now.

Hearing their stories of recovery can help you imagine your own journey.

Read, watch and listen to stories from everyday Australians about the signs and symptoms they experienced, how they got support, and what they do to stay well now.

Hearing their stories of recovery can help you imagine your own journey.

What a panic attack feels like - Milli's story

Panic attacks can affect people in different ways. Milli takes us through what a panic attack felt like for her, why she started having them, and how she got support.

Read moreIframe content loading...

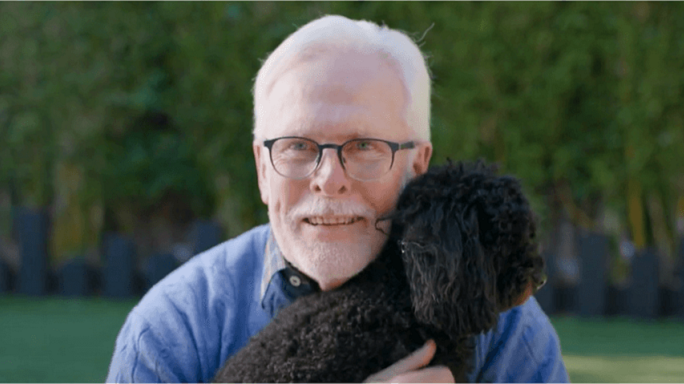

Stories from the LGBTIQ+ community

Sharing personal stories fosters connection, support, and understanding within the LGBTIQ+ community.

Here, individuals share their journeys, highlighting both the challenges and triumphs they have faced.

Share your story

The personal stories shared here feature Beyond Blue community members from our Speakers and Blue Voices programs.

If you would like to share your story, get involved today.

If you would like to share your story, get involved today.

You can also anonymously share your experiences and chat to our welcoming peer support community on our online forums.